Overseas Studies and Dispatches to and from Tokyo Academy of Music during the Meiji Era

What was learned from foreign countries?

The theme for Geisai 2022 is “Touch”…

Geisai 2022 (Tokyo University of the Arts Festival) will be held from September 2nd to September 4th. As a special program in conjunction with this event, GEIDAI Archives will introduce exchange students, both Japanese and foreign, during the Meiji era who “touched foreign music”.

Many students at the University of the Arts are studying abroad. However, how did students study abroad during the Meiji era when the social backgrounds, infrastructures, and people’s values were so different? This program takes a little peek into the student’s study abroad experiences through the examination of historical documents.

- From Tokyo Academy of Music to Studies in Europe and the U.S.

- Studying at Tokyo Academy of Music from Abroad

1. From Tokyo Academy of Music to Studing in Europe and the U.S.

0. Shūji Isawa’s Overseas Studies in Boston (Bridgewater Normal School)

Shūji Isawa (1851-1917), who later became the first principal of the Tokyo Academy of Music, joined the Ministry of Education, served as principal of Aichi Normal School, and went to the United States in 1875 for “Investigation of Education”. It was during this study abroad trip that Isawa began to formulate a plan for a music research facility.

He entered Bridgwater Normal School in the Boston suburb of Massachusetts. In his memoirs, he wrote that he was able to somehow get by through standard subjects and the study of foriegn languages, but music was the one thing he really struggled with.

“It has been generally assumed through previous biographical writings that Isawa, myself, was very proficient at music. However, the opposite is more true. I generally struggled at reading notation. Only my ability to produce the solfège “Do” and “Re” was consistently good, but my “Mi” and “Fa” seemed to always be too high. Even though I was scolded by my teachers and put in lots of hard effort to make corrections, I still rarely sung these scale degrees correctly.”

(東京藝術大学百年史刊行委員会編『東京藝術大学百年史 東京音楽学校篇 第1巻』, pp. 13-14)

One day, the principal called him in and said, “It’s not surprising that you are struggling with music class because the Japanese tuning system is so different from that of the U.S. From now on, we will exempt you from music class”. However, if he was exempted from the class he would not be able to return to his country, and this realization caused Isawa to cry and grieve for three days.

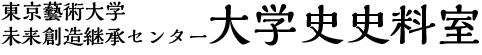

However, determined to not give up, Isawa visited L. W. Mason (1818-1896), an elementary school music director and teacher living in Boston, and took lessons at Mason’s home every Friday to overcome his weakness. This experience inspired Isawa’s desire to establish a teaching method for music in Japan. After returning to Japan, he jointly proposed with Tanetarō Megata and others to the Ministry of Education to establish the Music Investigation Committee (the predecessor of the Tokyo Academy of Music), and was appointed in charge of the Music Investigation Committee, and at the age of 36, later becoming the first principal of Tokyo Academy of Music. Isawa played a pioneering role in many aspects of modern Japanese education. Mason was later invited to join the Music Department as a hired foreigner.

1. Koh Kōda’s Study Abroad in Berlin (Musikhochschule Berlin)

Violinist Koh Kōda (later Koh Ando), Rohan and Nobu Kōda’s younger sister, studied in Germany under master Joseph Joachim, then the principal of the Berlin University of Music.

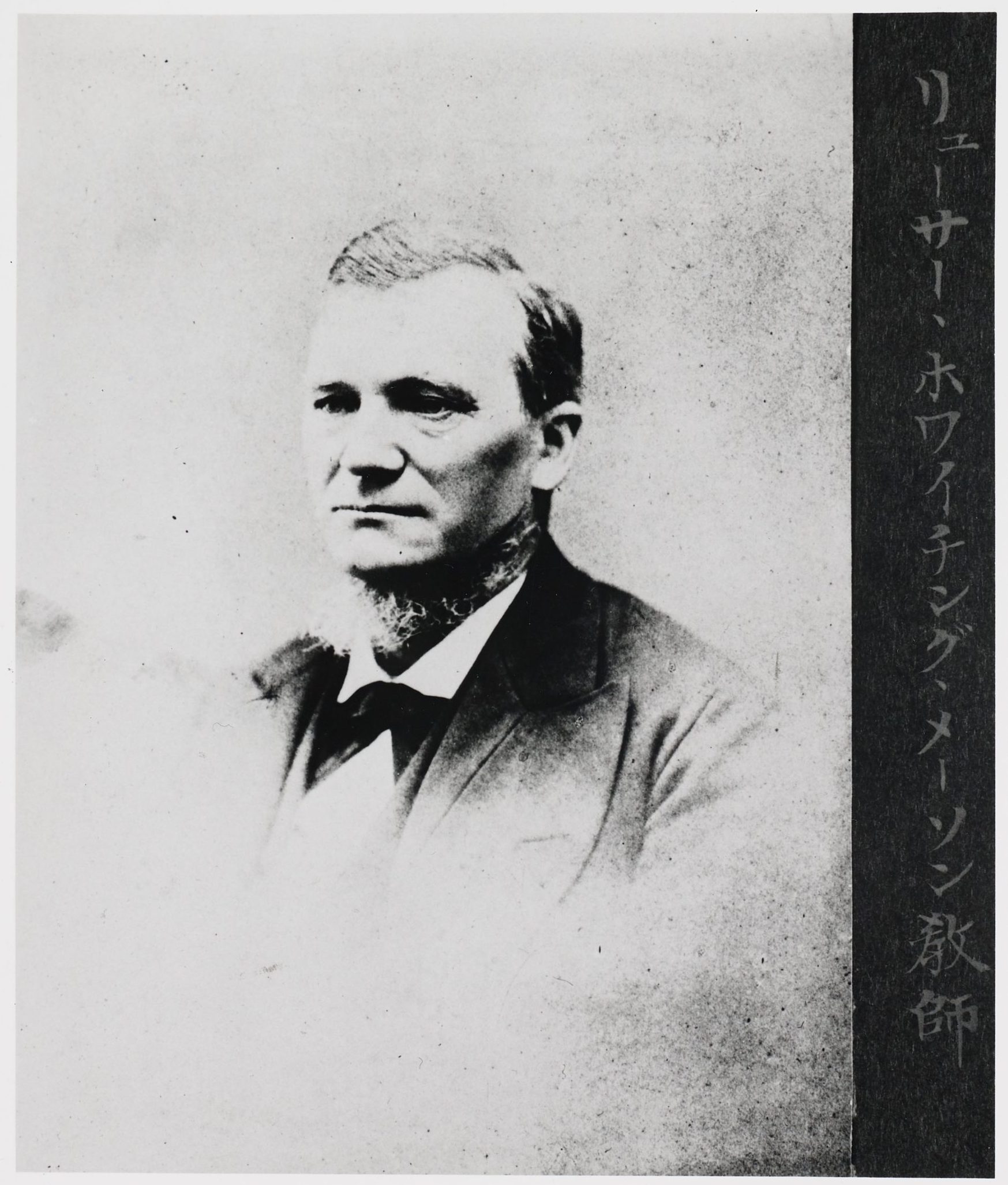

On September 3rd, 1899, Koh arrived in Vienna. In April 1902, she entered Berlin College of Music and extended her period of study for about three months at her own expense. She studied under Joachim and his student Carl Markees until December of the same year, as was reported in Koh’s “Study Abroad Reports,” (from “Documents Related to Overseas Researchers, 1900~1934”).

Koh wanted to study with Joachim, but only the most talented were given that honor. At that time Joachim didn’t have any students, and told Koh that if he wanted to study with him he would need to take the entrance exam at The Berlin State School of Music, which Koh successfully passed. After a year of study with Joachim’s assistant, Carl Markees, Koh was able to take lessons with Joachim. Joachim’s lessons were more often given by playing the violin than through direct instruction. She studied hard, attending not only violin lessons, but also practical piano, chamber music, and orchestra lessons, as well as harmony and counterpoint. She was also friends with Rentaro Taki, a junior student at the academy who was also studying abroad. (萩谷由喜子著『幸田姉妹〜洋楽黎明期を支えた幸田延と安藤幸』, pp. 129-132)

Koh’s sister Nobu also studied at the New England Conservatory in Boston for one year and at the Vienna Conservatory from 1890 for five years, where she majored in violin and also studied piano and harmony. In Boston, she studied violin with Emil Mahr, a student of Joachim. In later years, she looked back on her earliest impressions coming from hearing the performances of Nikisch, Dalbea, Hecking, Sarasate, and others. (東京藝術大学百年史編集委員会編『東京藝術大学百年史 東京音楽学校篇 第2巻』, pp. 1315-1316)

In Vienna, she studied with Hermesberger II, who taught Fritz Kreisler and others. She studied piano with Friederike Singer and also, because she felt like the harmony she was learning in school wasn’t enough, counterpoint and composition privately with Robert Fuchs.

2. Rentaro Taki’s Study Abraod in Leipzig (Leipzig Conservatory)

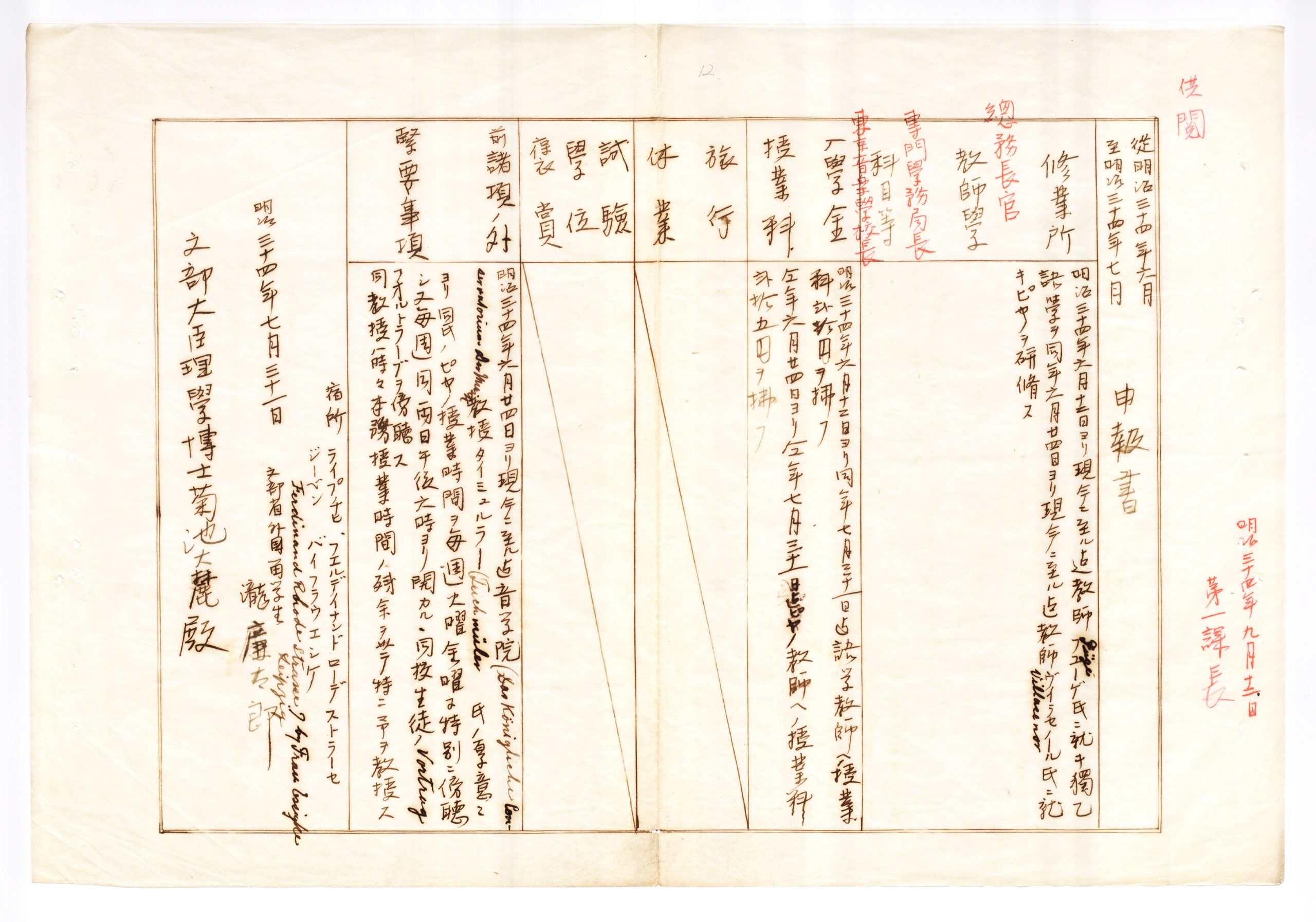

In June of 1901, Rentaro Taki also went to Leipzig, Germany, to study for the entrance examination for the Leipzig Conservatory of Music, which was to be held on October 1st.

He studied German with his teacher Mr. Fuge and piano with Mr. Villasenor. However, before entering the Leipzig Conservatory, his report on his studies abroad stated that he had also received piano instruction from Robert Teichmüller, professor at the Leipzig Conservatory. Taki was a devoted student of piano lessons, etc. It is clear that Taki was an enthusiastic learner during his lessons, explaining why his teacher was willing to teach him during their spare time.

“Professor Dr. Timmuller kindly allows us to observe his piano classes on Tuesdays and Fridays, and to observe his students’ vortrag at 6:00 p.m. on both Tuesdays and Fridays. The professor sometimes teaches the students in the Vortragforschung, using the remainder of his class time for special instruction.”

(“Rentaro Taki’s Report”, June 1901 to July 1901)

He then successfully passed his exams and was admitted to the Leipzig Conservatory. At the conservatory, he studied piano with Teichmüller, counterpoint with Jadassohn, and music history and aesthetics with Kretzschmar.

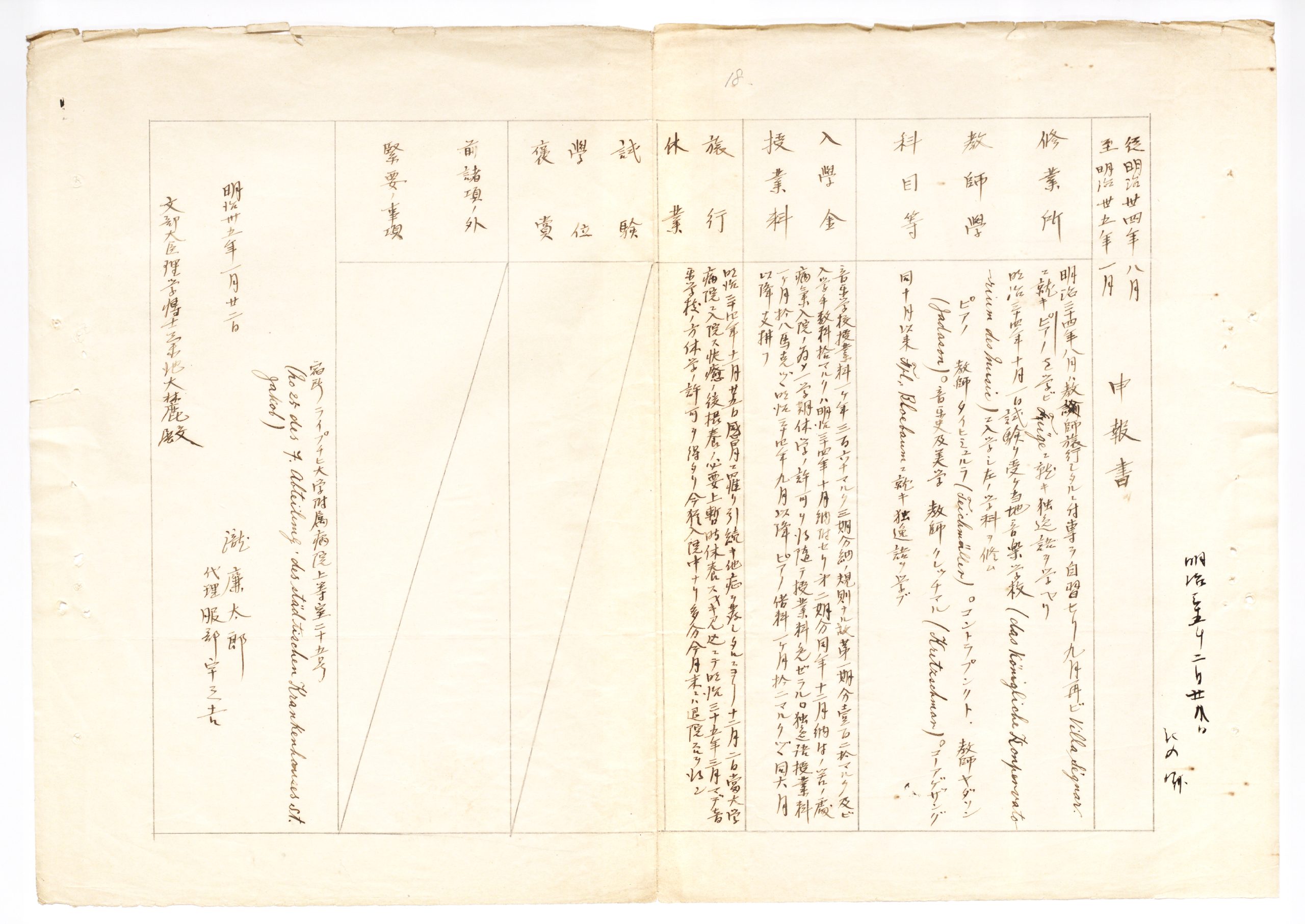

However, Taki was forced to be hospitalized at the end of November due to a persistent cold. In fact, in the application form dated August 1901 to January 1902, which was handwritten on his behalf, his lodging was listed as “Leipzig University Hospital, Upper Room, No. 25.

By July 1902, he was ordered to return to Japan, and after returning to Japan, he devoted himself to recuperation with his parents in Oita but he passed away in 1903 at the age of 23 years and 10 months.

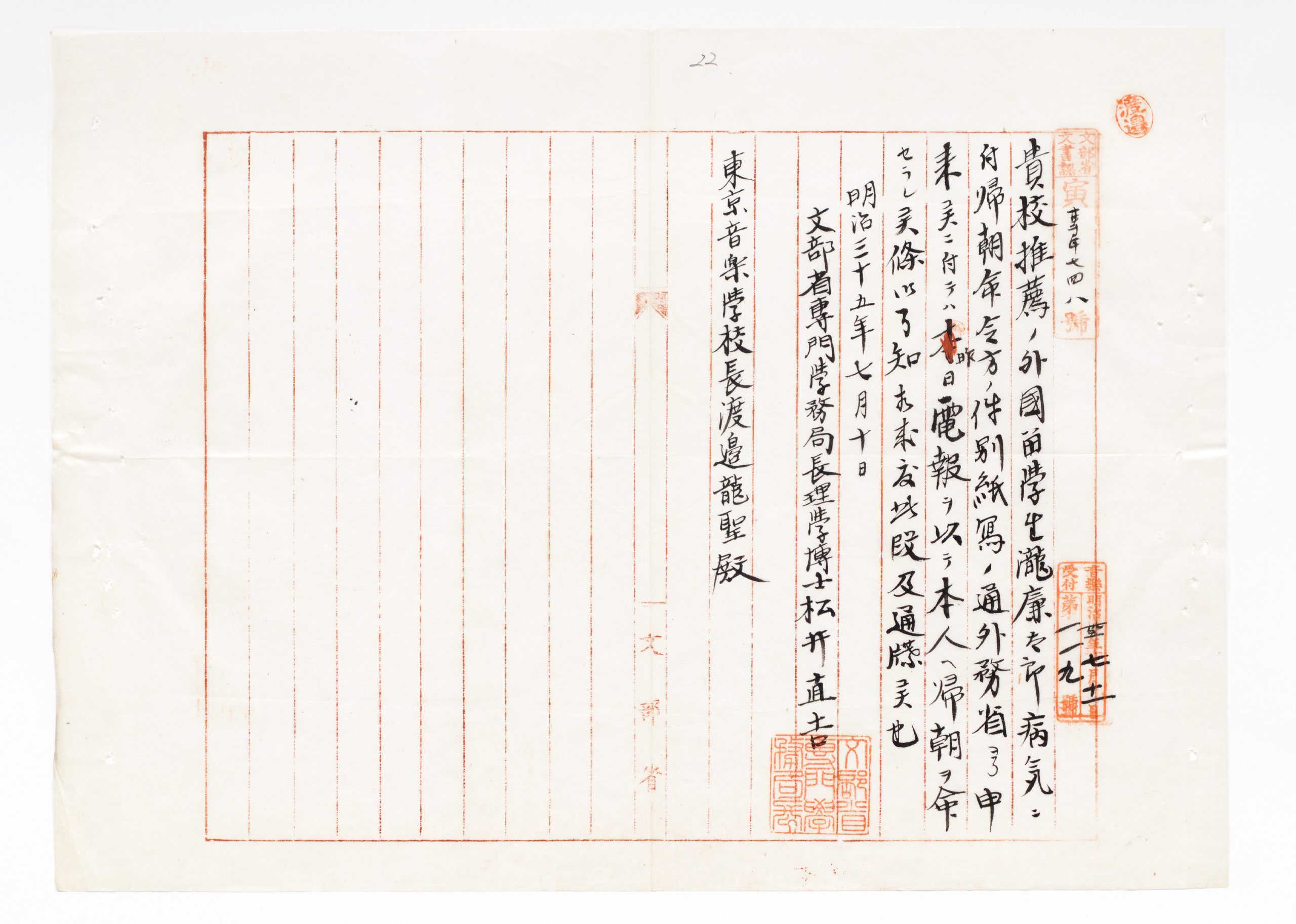

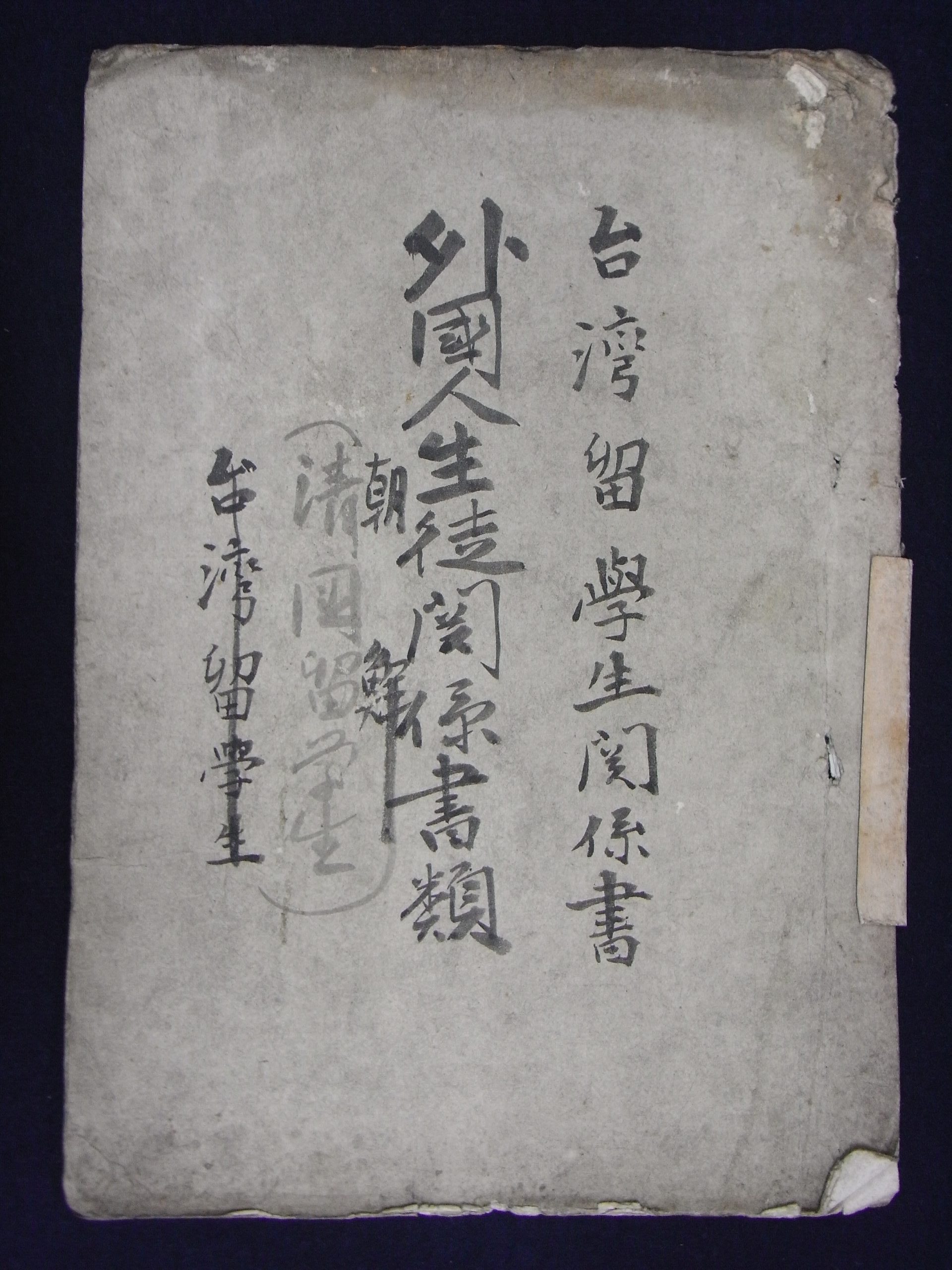

2. Studying at Tokyo Academy of Music from Abroad

In fact, many foreign students studied together with Japanese students at the Tokyo Academy of Music. It may seem a little surprising that there were foreign students coming from abroad to study Western music in Japan, far from the home of Western music.

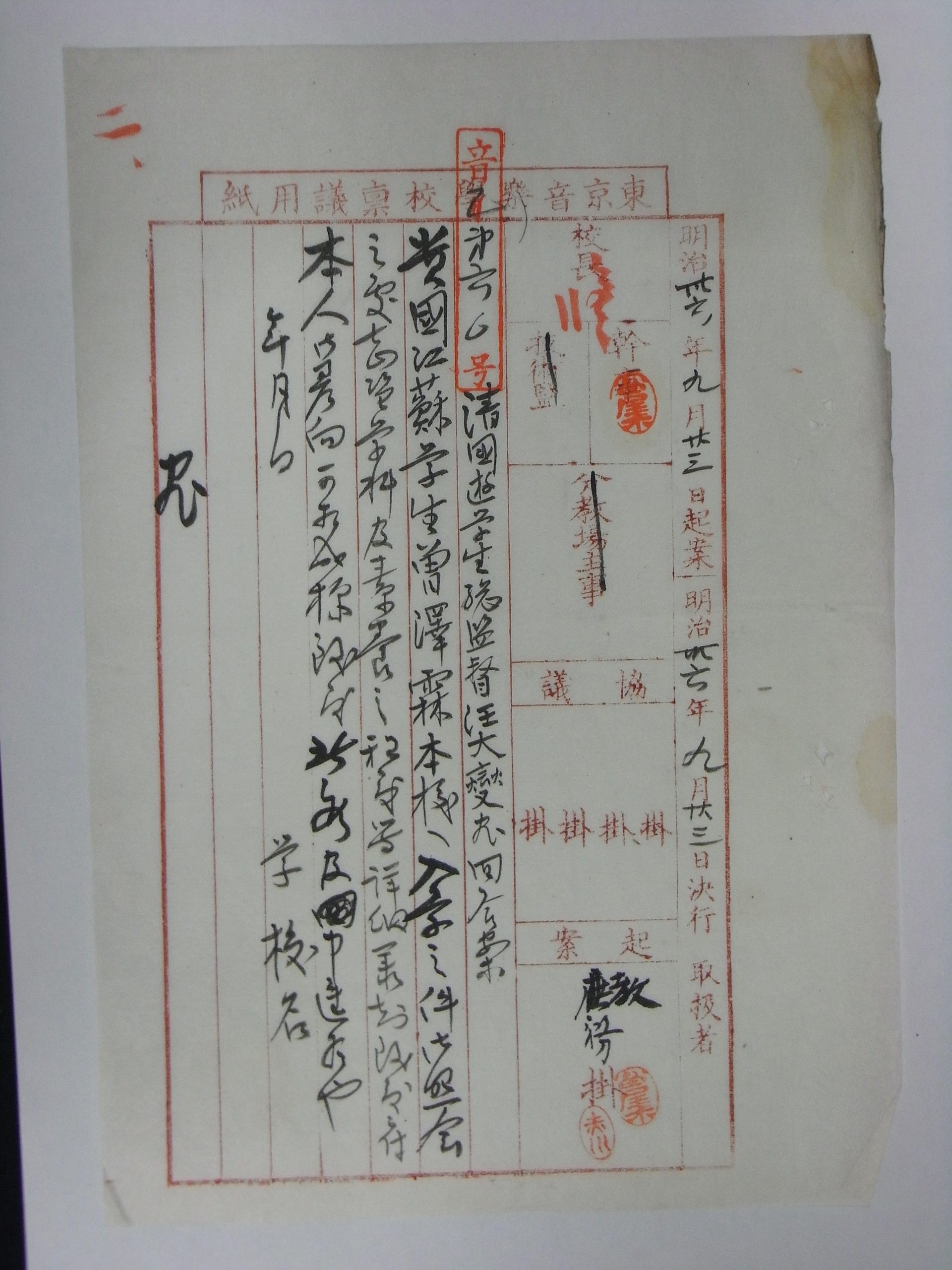

The “Tōkyō Ongaku Gakkō Ichiran (Tokyo Academy of Music Catalog),” which lists the names of students enrolled at the Tokyo School of Music, also includes the names of students from “China during the Qing dynasty,” “Korea,” “Taiwan,” “Philippines,” “United States,” “United Kingdom,” “Germany,” and other countries. In addition, administrative documents related to foreign students are compiled in “Documents Related to Foreign Students from Taiwan (Korean and Chinese students),” which mentions 57 foreign students, including, for example, Zeng Zelin(曾澤霖)— better known as Zeng Zhimin(曽志忞)—, an activist of the School Song Movement and an important figure in the history of modern Chinese music.

At the time, Japan was actively attracting foreign students, and the Chinese also welcomed the idea of their students efficiently studying in Japan. Furthermore, after the abolition of the system of enrollment in 1905, the Chinese faculty emphasized study abroad as a qualification to replace the system of enrollment, and the number of students who studied abroad continued to increase exponentially. It was against this background that many Chinese students came to the Tokyo Academy of Music. The majority of Chinese students were elective students, many of whom were concurrently studying music and another specialty such as fine arts, politics, science, or medicine, and many were also enrolled at other schools. (尾高暁子著「留学生管理文書の概要」「附論:旧東京音楽学校管理文書にみる外国人・外地生徒」、『東京音楽学校の諸活動を通して見る日本近代音楽文化の成立:東アジアの視点を交えて』, pp. 316-328)

References

東京藝術大学百年史刊行委員会編『東京藝術大学百年史 東京音楽学校篇 第1巻』、音楽之友社、昭和62年。

東京藝術大学百年史編集委員会編『東京藝術大学百年史 東京音楽学校篇 第2巻』、音楽之友社、平成15年。

萩谷由喜子著『幸田姉妹〜洋楽黎明期を支えた幸田延と安藤幸』、株式会社ショパン、2003年。

尾高暁子著「留学生管理文書の概要」「附論:旧東京音楽学校管理文書にみる外国人・外地生徒」、『東京音楽学校の諸活動を通して見る日本近代音楽文化の成立:東アジアの視点を交えて』、平成25年、pp. 312-356。